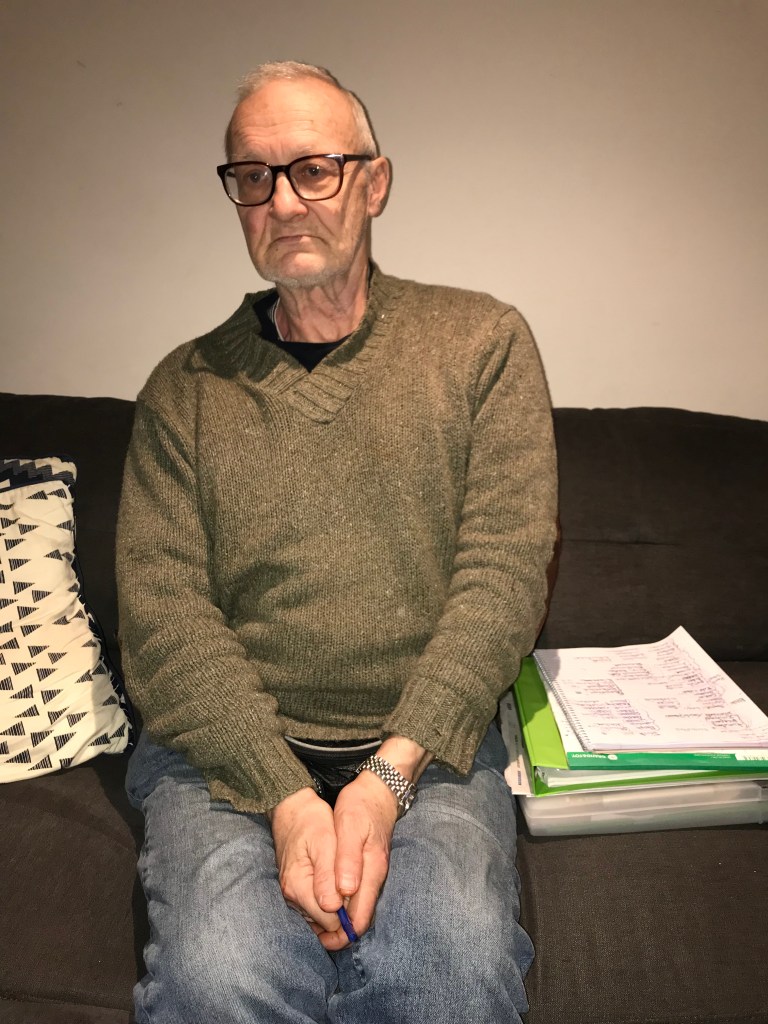

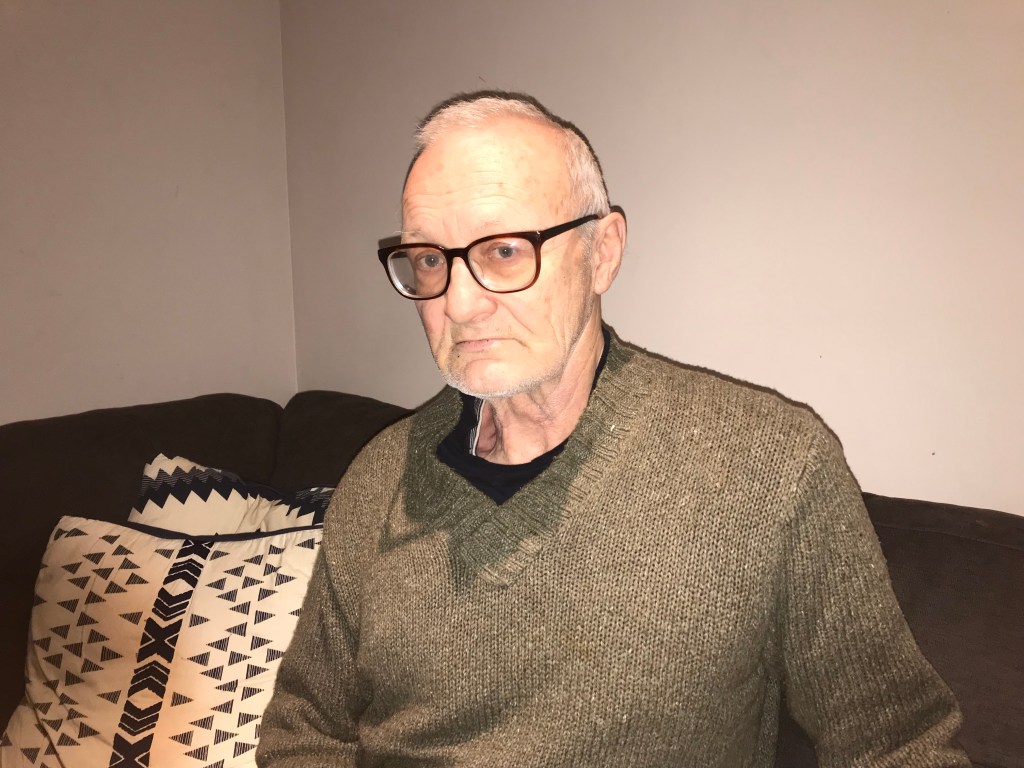

Bob, 75

My Life in a Nutshell

- I’m a widower and retiree who lives in rural Northern Ontario, and come from “the last generation of frontier people.”

- I care about my family: “I’d like to see them happy”

- I wish people cared more about the truth

- I look back fondly on my childhood, “because my family had a large general store and there were still a lot of people in the community. We used to have a lot of good times during the holidays, Easter, Christmas and so on. We used to go blueberry picking together and all that”

- I love to draw and paint and wanted to be an artist, but I never pursued it because “it seemed frivolous”

- my wife and I faced discrimination because people weren’t as accepting of interracial marriage in the 1970s

- my greatest regret is I that I didn’t “treat my wife better,” I didn’t understand how PTSD from her childhood impacted her throughout her life

- I was an Olympic-calibre athlete but suffered a severe spinal injury

- I was once an atheist but now believe in God

- I built my family home and I built my cabin single-handedly

- my life became a disappointment but I am still “basically happy”

Bob’s Story

Bob’s face is bristled with a light dusting of white whiskers, his hair, what remains of it, is trimmed close to his head. He is not a frail older man; nor, however, is he glowing with health. He is well-built, though, particularly for a 75-year-old man, despite the fact he appears fatigued.

When I sit down with him he is writing notes in lined a notepad.

“I’m making lists. This one is about all the foods I can grow in my garden. This one is about new research, new ideas. You can always find an interesting book, some of them on cancer.”

Bob reveals he has battled cancer this year, and spent nine months receiving chemotherapy and other treatments.

“From the time I was a little boy I always liked to have warm feet,” he says. “Now that I had chemo for cancer I’m having trouble with cold feet.”

Bob says he discovered some lumps in his abdomen and groin more than two years ago, but he ignored them until he experienced a “severe pain” last December. He went to see a doctor, and a slew of appointments with specialists soon followed. Bob would learn he had lymphoma just after Christmas.

“It was hard to endure, but I never doubted I would get better. And when I learned to pray and asked God to heal me — it just disappeared. I can’t say for sure that God healed me, it could have been the medicine, but everybody was surprised, including the oncologist.”

Bob finished chemo this summer, and just last week had his three-month checkup. Thankfully, there was still no trace of cancer in his body.

“I was surprised, I was expecting to go through radiation therapy.”

Cancer is a terrifying diagnosis, and chemotherapy is notoriously unpleasant. Still, this is not what Bob would describe as the greatest hardship he’s ever endured. He says he suffered a spinal injury when he was at a track and field meet in high school, and for a short time he couldn’t walk.

“I had this terrible fear. I realized: ‘I’m paralyzed. I’m not going to live this way. I’m going to kill myself.’ My intention was to hang myself, because I could still do that.”

But Bob says his back miraculously repaired itself. Once again, he credits God for his recovery.

It is an interesting turnabout, for a man who was a self-admitted atheist most of his life. Bob says he only became religious in the last few years.

“I learned how to pray. So my prayers can be heard in heaven.”

While religion currently preoccupies him, Bob’s life has been one of exploration — both literally and figuratively. He loves books, reading and reflection, but he also loves the outdoors. He has lived across the country, in both rural and urban settings, and has had a variety of careers — from landscaping and forestry, to owning and operating a restaurant and two corner stores.

“I wasn’t particularly interested in anything, so I just wandered around from one thing to the other, to keep from getting too bored with life.”

Bob actually met his wife of 35 years when he was the supply manager in a hospital in small-town Ontario.

“She came here as a nurse. She’d been in Newfoundland and she was lonely. There were no Koreans there and she could barely speak English. So when she heard there were some Korean girl nurses in the hospital where I was, she came over.”

They married ten months later. He built the home they lived in when she was pregnant, and their first child was just an infant.

“I started in August one year, and I finished it in the spring, the next year, because we moved in in June.”

I express surprise that he built the family home, a four-bedroom with a greenhouse, completely on his own.

“Well, in the country, people did most of their own building,” he says. “I like working with groups of men outside. I used to get involved with building, watching them, working on barns and that sort of thing.”

Bob describes his marriage as having many highs and lows. He says his wife lived through the Korean War and suffered from PTSD, something he wishes he’d better understood when he was younger.

“If there was 50 ways to go from point A to point B I would want to take every one — one after the other — to see what was there. But not her. She had to always have the exact same routine, or she would go nuts. She couldn’t take any stress.”

Bob says he and his wife could not have been more different. He had a “happy childhood”, while she grew up in wartime and lost her father. She was also from Seoul, a huge city, while he was born and raised in rural Canada.

But when they met, he says, “there was instant recognition.”

Still, while he never “thought a whole lot” about the fact his wife was a different race, he says others did question their decision to marry.

“Because it wasn’t that common.”

He says, at times, they faced discrimination — and it didn’t matter if they were living in a small town or a larger city. And they faced condemnation from both caucasians and asians. Thankfully, he says, people’s attitudes are changing.

“It’s becoming more common, interracial marriage.”

His wife died 15 years ago, from pancreatic cancer.

“Oh, that was difficult. But the marriage was slowly coming apart because we had such different backgrounds,” he says. “I didn’t really adapt well to living in the city because all of my education was in forestry and agriculture.”

Still, he lists getting married as a highlight of his life, along with the moments his two children were born.

Now, he says, his greatest hope for the future is: “to live long enough to see my grandkids growing up.”

And while he says he has regrets, and has “often” made bad decisions, he is content.

“More or less. I don’t know if I ever knew joy, but I’ve always basically been happy.”

Bob is currently retired. He owns a home he shares with his sister, often visits a cabin he built himself, and lives surrounded by close family.

“I’m just another face in the crowd, that’s all. I’ve never been important,” he says. After a short pause, he adds, “I never wanted to be.”